"A STORY OF NORTHERN LIFE"

from the book

"Beyond the Circle"

by Leo Trunt

Published with Permission of the Author

Transcribed by Karen Klennert

For Purchasing Information, Contact Leo Trunt

Much of Gray's memoirs deal with his life in Iowa, and the western parts of the United States. He spent the last years of his life in northern Minnesota, more specifically in the Swan River and Jacobson area. In an effort to show how one man lived after the turn of the century, this portion of his memoirs is now recorded for posterity. Gray lived life to the fullest. He had sampled different ways of making a living such as being a farmer and cowboy out west. He wanted to see the "Great Northland" and so he began the life of a trapper, logger, and game hunter. While Gray states that he came in 1902, he is listed in the 1900 census of Ball Bluff Township. The enumerator states that Gray is 25 years old with his occupation as a river driver. As the memoirs were written about 1910, the writing characteristics are somewhat different than today. Some corrections were made by the editor in the areas of grammar and spelling. Most of the original text was kept to maintain the spirit of the memoirs.

The fall of 1902 found me making my way for the cold regions of the north for an old time hunt in the forests and hills. My plans were to trap all winter and the following spring.

As I had been out a few times before on small hunts, I was not altogether a tenderfoot, yet this was my first attempt at a good old time style hunt, many miles from friends. Had I had a partner or friends, it would not have been such a task. (I was) striking out for the wilds with no friends, but hostile natives whom I became acquainted with in the following story. (And so) I struck out as an old time hunter and trapper to wilds unknown, to a climate very cold, where long hard winters have to be withstood as well as the many hardships and troubles that make the trip one of adventure and interest. Were it not for the hardships, there would be very little adventure. Of course, I realized the fact that a good partner would make it more pleasant, but my partner was at home working in a bakery owned by his father, so I went alone.

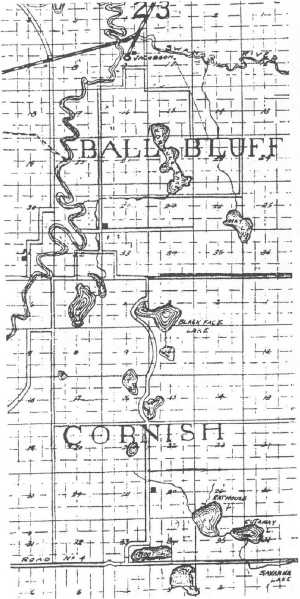

Early Map of Ball Bluff and Cornish Townships

Courtesy of Aitkin County Land Department

I will not encumber this story with everyday doings, but I put in a fine winter. When the snow got deep, I made me a pair of snowshoes. When the crust got hard on top, I made a pair of skis, and if I could get a long slope of ground, I could keep up with a rabbit.

I made trips for miles out to small settlements for a chance to see someone once in a while. I sent out my furs two times during the winter and once in the spring. My catch was not so large, but the price being higher I did pretty well, shipping my fur to Percy & Co. Fur House in Oshkosh, WI. I always got the worth of my fur. I got the price of fur every month by mail which kept me posted.

I killed only one wolf this winter that had been eating one of my deer I had in the woods. He was standing on a stump about fifty yards from me, and for luck, I took a pop at him. I struck him in the neck, breaking it, and he tumbled off the stump. He would chase the deer no more. There was seven dollars bounty on him and his hide was worth six dollars. A lucky shot for thirteen dollars. I wish I could have a shot at one every day.

Late in the spring I was getting ready to ship my last batch of furs. It was about the first of April when one day, I discovered a huge track along the ridge below the camp, and on examining it closely, I found it to be a bear track. I had seen a track the fall before, and I now began to plan his capture as it would help out my pocket, as well as having the fun of killing a bear. I discovered that he had been there several times. I followed up a little and found where he had been tearing up the snow, grass and dirt. I found that he had something buried there or else it was an old horse that had been left there. I finally set a bear trap for him by building a rude enclosure so he could get to his cache by only one way. Here I set the trap. I also thought of setting a gun for him so he would shoot himself, but this I omitted. I also bore a hole in a log close by, big enough for him to get his claws in. I then bore a hole on each side, slanting into this latter hole. In these I drove hardwood pins well sharpened in solid and nailed them there. I went to camp, procured a quart of syrup juiced in about half. When the bear got a taste of the sweet, he would go daffy and plunge his whole fist into the enclosure. When he wanted to remove it, the pins would catch him on each side, and the harder he pulled, the tighter he would be. He could now rave and tear, but he could not handle a big birch log unless he tore out the side of the log and that would take some power.

Every morning I went to my bear haunt, but he wasn't there. I had nearly given up, when one evening about eight o'clock (I was just cleaning up the dishes), I heard the worst racket and from the noise came to the conclusion I had a panther, bear or some other big animal. I made me a pine torch, took my rifle belt, knife, and hunting ax and started out on the war path with Beaver (my dog) by my side for he was almost crazy with excitement. I was just one hill away, and if I ever saw a vicious animal, this was it. He looked like he could swallow me at one bite. I guess he would have done something if he had got a hold of me. He didn't show any mercy whatever, for the nearer I got, the madder he got. My, but he did tear around there. When the dog came up, he didn't pay any more attention to me, but was after the dog. Beaver didn't know what to make of him, for it was the first bear he had ever seen, but he found out when he got a little too close. Mr. Cinnamon Bear rolled him about twenty feet head over heels, and Beaver did not get so close the next time. I hated to kill the poor brute, but that was what I caught him for. I wouldn't wish to be near when he got his foot free from that birch log. So I said now or never. I raised my rifle, held the torch in my left hand so I could see, and took good aim just behind the ear and fired. He let a noise out of him and pawed the air for a few minutes, but my rifle was too much for him, and he finally fell over struggling his last.

I now had a change of diet which was bear meat. I was sorry he wasn't a black bear for he would have been worth more. Brown bears being worth only $10.00 to $15.00. Black bears from $15.00 to $30.00. I was now a bear hunter, but failed to see any more.

After I had shipped my last lot (of furs), I rested up for a few days and then packed up what I wanted and hid the rest until such time as I wanted them. I went up to the Chippewa Reservation on Big Sandy Lake with my Indian friend whom I knew as Charlie Chin. I stayed with the Indians awhile and watched them tan deer hides and bead moccasins. I had them make me a buckskin suit and a pair of moccasins for next winter. I was out hunting and fishing with them and soon got well acquainted and learned to understand the Chippewa language. I learned to talk it a little. They called me their paleface brother. You could hardly have known me from one of them in my buckskin suit and tanned face.

When the river began to warm up by the spring sun, I went out to look for a job for a few months. I finally landed on the Swan River by way of the Great Northern Railway. I started to work here for a man by the name of J. C. Patterson, whom I called Captain Jack. He was getting out cedar, oak and pine ties, logs and poles. I was now tackling a new business that I knew nothing of. I was a fellow that loved adventure and I was always ready to try something new.

Swan River Logging Company's Log Landing at Mississippi Landing in Jacobson

Courtesy of Walter Schularick

I started to work for thirty dollars per month. He had the timber all ready on the banks of the Swan River. All we had to do was to raft them. Every morning by day light found us on the river banks. First a pine or cedar was rolled to the edge of the bank and then two strong ash poles were secured, one on each end of the log by means of chain dogs, which are a couple of flat stakes joined together by a short chain. One of these were driven on each side of the white ash pole into the log. Then a coil of rope was secured, one end tied around the pole and at the end of the log, then another around the other end of the pole which was about thirty feet long. The first rope was given to a man who either tied the rope across the stream, or if in a bend of the river, where the swift current was just slight. He secured it to a tree on the same side, the object being to get the frame into the middle of the stream and still have the log straight with the stream. The first hand at rafting after the log was shoved off the bank (sometimes six or ten feet steep) would make water fly. The man was to jump on the log with a hammer scherin dogs and a fury. Another with a peavey rolled in the tied logs, or whatever was to be rafted, and another caught the timber as it came down stream. By hard steady work, it was guided under the claris poles where it was fastened as the first. If you were sent a good hand about the time a timber struck the log you were on, you would likely go overboard in the ice cold water and thus hear your partners laughing at you, what without anything even striking you in the swift current. Your nerves would fail you by the constant rocking of the water, and every time anyone would move, the log would be sure to sink in the swift stream.

After we had built a raft large enough to turn around in the river, one of us would board it and run it downstream some distance and by means of ropes were able to tie it along the bank. The first time they sent me down, I snubbed up the raft too quickly and "whack" went the rope. I had taken pains to land there by jumping for the bank, but instead of making shore, I went into the river up to my arms which nearly took my breath as it was pretty cold. It was nothing after you learned the trade, running along the bank in mud to your knees, snubbing the raft to trees until you got where the stream wasn't so swift.

Swan River was noted for its swift current. A person could drift seven miles an hour in the steadiest water. When you struck rapids, of which the river was full of, I don't know how fast we did go. I know when we struck a rock, it would mash the raft to splinters. When you were sent to tie up a raft, it was your duty to get it to shore in a certain place. You had to get it there the best you could. Snubbing up a large raft in a swift stream is likely to cause a little effort on your part with care being taken not to get your hand in the rope. If you did, it would grind them to meal. If the rope busted, your work was all in vain, and you would have to board the raft any way you could, splice the rope, and try again. If you were gone a little too long, you would be sure to hear from the boss. If you got hung up, you would have to jump in. Ice cold water was no excuse if you wished to hold your job. You would have to pry the raft off the best you could, though it seldom hung up unless in still water. When it did, you had to work to get it off.

You would get to camp about 9 o'clock, if not later. A fire and some coffee was started and then roll yourself in a blanket and sleep. After the excitement of the day, you may have "nightmares," where you would swim all night and wake up fighting for a raft on the rapids.

If you were going to build a raft across the river from camp, you would find a piece of drift wood and cross it. If you were in such luck as to be able to ride the log, you would do so. If you ended up in the water, you would likely suffer cramps in your legs from the cold water, but there is nothing like getting used to it. Be an all around tough guy while you can. That's the way we talk to a tender foot.

Sunday was no exception. We worked every day alike, rain or shine, wet or dry. Daylight in the morning was our time to start work. We had handled many heavy oak logs. Rolling them on the bank was hard work and picking up green oak ties was harder.

I received many a talking to for my mistakes. The more I would try, the more luck went against me. At first, I was mad enough to jump my job, but yet I felt guilty to experience such mishaps. I was losing axes, hammers, and peaveys every little while, but they were charged up to me, so it did not make any difference to them. They could charge me double the price if they chose, and I would not be the wiser.

Time was of the essence to go to one camp after another, and not at all slow, for there was no time to lose rafting. Everything went in a hurry. The boss was yelling at the top of his voice half the time. If one of us was too slow, he would turn us off and get another. It was very few who held their place, for a man had to work like a slave. A little bag on your back contained a little cold biscuit with meat and Oleo, which is a substitute for butter. You sat down and ate that when the boss yelled dinner. You ate it as fast as you could wash it down with a little river water, and then onto your feet again, sweating like good steel when you blow your breath on it.

When we stood waist deep in water fishing for an oak log that would not float but had sunk, it was work to get it up. In a cold down-pouring rain, the ropes and tools would get so cold and slippery. You would not soon forget such an experience. Next summer when the river dried up, we would fish up all the peaveys, axes, hammers and stuff and use them next time for someone else to lose. Peaveys cost $3.50, axes were $1.50, hammers were $2.00, and chain dogs were 15 cents a piece. Pick poles would sink but they would break easily when picking or steering rafts in the stones of the rapids, which were so numerous in this river and made the current so swift. My hair would stand on end every time I was going over the bad rapids.

One end of your raft would strike a rock so hard it would knock you to the other end, strike another, knock you back, and the raft looked like it was going to be torn to pieces. It would actually scream and groan with so much power behind it. It would swing around the rock with a sudden swish, and then go along at a swift rate. It would seem you were actually cutting the wind, and with the roar like thunder pounding over thousands of rocks, you could not hear yourself yell. In all, it was a dismal period. It was your duty to steer off of the biggest rocks. You would have to use your strength in guiding off of a certain rock long before you got there, for in such water a man's strength means nothing. Your raft would hit here and there, keeping the raft in a jumping motion all the time. If you would strike a double header, you did well to stay on the raft. You would go a half mile over such, you would think the danger was over, when all at once you felt a falling sensation. You would wake up to where you were, and then you struck the raft again and found you were stranded, run right up on top of a rock. The raft would be bulged up in the middle of the stream as that is where the rafts go, for that is where the current is. If you had any tools aboard you took care of them, for they were always in danger of being lost, and then charged to you, besides (receiving) a good lecture for getting hung up. I would not tell the reader what kind of language or lecture I got, but you can imagine how they talked.

If your raft was hung up solid, you were then supposed to get off in the water to your waist or your arm pits or whatever depth it was. The water was ice cold and the current so swift that it would take you off of you feet if you let loose of the raft. It was the order of the day to work and twist till you got it off, and not too long either, or the boss would be around. You would have to be careful to be ready to jump on it, for it would start when you least expected it, and would not wait for you to get on when it started. You should never work in front of the raft or down stream of it, for when the raft started, it would put you under and run you around and likely grind you into mince meat on the rocks.

If you did not get your raft off the rapids before another raft came along, in all probabilities it would either knock you off or else it would run on top of yours and make a worse mess than ever, and you had to be as spry as a wild cat to escape a broken leg if not a broken neck. We once had three rafts hung up right on top of one another. I took for shore in that swift rapids, and I got a few hard jolts on the rocks, but that just helped me along faster. We now had to catch the rafts following before they reached the rapids and tied them up.

Once in a while a man was sometimes left to take care of five or six rafts. If they got hung up, you were to jump from the one you were on to the one hung up. The rafts would pass each other if the space was too great. In that case, you had to get to it the best you could, always falling behind jumping all the day until you reached the mouth of the Swan River, where they were all tied up by means of a long coiled rope. Rafts were tied along both sides of the river in a string, and if one got away, you got a good calling down for not throwing the coil straight. Then a boat had to be taken down the Mississippi River, catch the raft and haul it into land. The Mississippi being so wide, it was no small job, perhaps taking two or three miles to get to shore for the water was very high in the spring. When there were two or three that were hung up so that one man could not get them off, we all went back, waded or swam to them and helped them off. Sometimes they had to be all torn to pieces. In that case, a boom was stretched somewhere so the timber was stopped from entering the Mississippi.

We worked until they were all at the mouth of the river. It was quite a sight to see long coils of ropes thrown from land to a raft coming down stream to be tied up. Then would come the job of taking four of these rafts or brills and tying, spicing the four in a square, thus making a very large raft to go in the Mississippi. In that way our number of rafts were reduced. Each night we had five or six miles to walk to camp and each day we would bring along some more rafts until the river was so full that it backed up the water above. When the work began to splice the rafts together, we took a tent and a lot of provisions and cooking utensils and camped near our work. When the last job was done, they were turned loose, a little while a part from each other, till it was in the great Mississippi. Eventually they were all gone, and we generally turned them loose about three o'clock in the morning, then by daylight we would start after them in a boat. After rowing hard a few hours, we would overtake the first one. One of us was left to ride on the last raft to follow up. One fellow was always left to watch camp, take care of the horses until our return, taking us about two weeks to make the trip to Aitkin. Every night we camped on the banks of the Mississippi.

When we got down the river, we occasionally passed a farm house where one of us would go and get some milk, eggs, butter, or whatever we wanted. Every morning about three o'clock found us rowing trying to overtake the rafts and get ahead of them.

When we got to Aitkin, the rafts were all caught near the mill, and by a little wet work, we got the stuff on the banks, oak logs and pine logs, oak and cedar ties, posts and oak pilings, and cedar poles. Much of the timber was forty or fifty feet long. When it was settled for, we got our pay, generally being about three months worth if we started at the beginning. We now went uptown, for we didn't see a town very often, to blow our stake. That is, those that wished to. If there were any who was stingy with their money, they were not liked by the crowd and in consequence got the worst of it, as the rule was give and take. The crowd of men would enforce their rules on all. They make a stake, the next day they are broke. A hundred dollars is nothing to them. They drink it up or gamble it away just as they please, then go back to work again.

It was a fine evening as we all went up the old foot trail, there being about a score of us. We made a pretty tough looking crowd, but nothing unusual in that wild northern town. Dressed in style, that is, lumber jack style. It was common to see a fellow coming down the street with a pair of driving boots corked on the bottom (that is full of spikes about a half inch long) which stuck to the sidewalk at every step. A lumberjack might have suspenders that were faded to all colors, maybe a leather belt, an old shirt cut off at the sleeves below the elbow, and an old hat with a dozen or more rifle holes in it.

Well, it was a fine evening as I said before, when the whole of us entered a barroom adjoining a hotel where we were going to stop overnight. Of course the first thing they wanted was a drink of genuine stuff or good whiskey. They did not stop at the first drink, but kept on drinking. Some would start to go when someone would yell, "Everybody drink!" and back to the bar they went. That's the way it was. They finally got so full, they were mad with whiskey. They even got the bartender scared and people were crowding to see what would happen.

Of course, I had learned to keep friendly with them, though I didn't drink myself. Finally, a tall large man stepped up to the bar, and with a voice sounding like a lion yelled. "Everybody forward! Drink! It's as free as the whiskey from the rye field! Drink, everybody drink!" Everybody went up but me. I was looking at a mixed pack of cards, when the big fellow got his eye on me. "Here boy, you come here, and get what will make a man of you. Don't take a back seat on such an occasion. I never allow anyone to be slighted when Uncle Joe is around." He walked up, took me by the collar, and led me to the bar.

"What's yours?" asked the bartender.

"Water, please," I said.

"Listen at that will you!" said the Big Jack. "Didn't you get enough water in the rapids when you got dunked? Are you really kid enough to dare to say water when I'm around?"

"I don't need such a strong stimulant as you, Uncle Joe, so you must excuse me," I said.

"Excuse you, the devil you say. Drink or by Joe McStalla, I will pour it down you. I say again to drink." He was getting raving mad now, for he was full of whiskey to the brim. I started to walk out. "Stop there you little devil, or I will put two holes through you while you are turning around! Damn you little stupid devil! If you know who you are going against, go ahead!"

The rest had crowded in a circle for they were expecting to see some fun. I had seen a large Colt forty four in the big man's hand, and from his looks, he meant every word he said. My comrades were foolish enough themselves with whiskey so they were ready for some excitement. Big Joe ordered a glass of the finest stuff in the house for me, but I declined to drink.

I said, "Drink it for yourself, Joe, for me." I saw his eyes flash, and his hand grip the butt of his weapon. "Don't you do it, Joe. You will get the worst of it in the end," I said.

Bang-bang! went the weapon faster than you could count. "You dance, you Devil! I will shoot off your feet by inches! Dance, I tell you!"

"I can't dance, " I said, "And I won't dance for a drunken fool like you, and I mean what I say. Drink that glass. You tend to your...." Bang

The crowd was yelling amidst the smoke. "Stop shooting off my boot heels. They cost money and I ain't going to have them shot to pieces by such as you. I don't have $7.50 every day to buy shoes, " I said.

While he was the worst he could be, as quick as a wild cat, I knocked the weapon out of his hand. It exploded as it fell, but was harmless, no damage but the hole in the floor. I didn't wait to see much, but with one bound, I was clear out the door and into the darkness of the night.

I was glad to get away. I made for the river, found our boat, and ate lunch. It was now far into the night. I took a couple of blankets, went off into the pasture, rolled up in my blankets and went to sleep. The day had been a hard one on me to say the least. The excitement didn't bother my dreams any, as I was too tired to realize the danger in such a crowd of drunken maniacs. When I woke early the next morning, I found some of them in the boat, and the rest were scattered all over, dead drunk.

This was my first such experience with such a mob, and I was glad to leave the place. I took the steamer up the river. I stopped off at the Sandy Lake Indian Reservation. The man that owned the steamer also sold whiskey to the Indians, which made them pretty noisy. It made them wild and you could hear them yelling all night long. The boat stopped over a night at every trip, and the Indians would spend their time drinking. I spent a pretty good time there, getting them to tan a couple of buck skins for me. I found these Indians very friendly, and they treated me as an honored guest. I also was honored with their great feast, which is nothing more than good, healthy, fat dog meat. I had a good time with this tribe of Indians, and they invited me to make them a visit whenever I felt like it. I had learned their dialect or language, and in that way, I was soon a friend of the tribe. I also had the pleasure of seeing them make a birch-bark canoe.

I finally left there, took a steamer up river, and arrived at the logging camp. I stayed around here all summer, doing nothing but hunt and fish.

Early Logging Efforts on the West Side of the Mississippi River in Ball Bluff Township, 1906

Courtesy of Walter Koski

About the first of August, I went out to the settlement (Swan River) and worked at a hotel cutting wood, working in the garden, taking care of stock, and other work in general. The mosquitoes got so thick down on the river, I got sick of fighting them day and night. The flies were so bad that the horses had to be kept in a dark barn all day. If you took them out to water, when you got them back to the barn, the blood would just be running off of them. July and August were the only bad months, and you would hardly see one before or after that time.

Thomas J. Feeley's Hotel at "Old Swan River"

Leo Trunt Collection

The mosquitoes were actually so large and thick they would nearly darken the sun. They seemed to come in a cloud. You could hear them most all night up in the sand hills, but the nights being so cold in the north they did not last long.

I worked there until the mosquitoes were gone, and my old boss came and asked if I wanted another job rafting. I had said that I would not raft again. After a long sociable talk, I said I would not have it so hard this time, and I also wished to hunt with Captain Jack. The coming fall I again hired out for $1.50 a day. I was now considered a fair hand at rafting. The boss was just going to take a small raft, as it was late in the season. We had the same old trick over again as before. They had lifted the gate at the dam on Swan Lake and were going to drive them through into the Mississippi.

I didn't expect to go to Aitkin this trip. I had a fine job this time. Twice a week I had to go to the settlement and pack provisions. It was eight miles to the settlement by an old Indian trail, which made it sixteen miles every trip. Sometimes I had eighty pounds to pack, which got pretty heavy by the time I got to camp. I was through with work by the last of September. Since the dam was opened already at Swan Lake, I struck out up the river to the lowest driving camp. I hired out as a driver, but had never ridden a log before, only when I was rafting.

They soon found out that I was green at the job, but a fellow I got acquainted with helped me out. I worked along with him. I was ready and willing to learn, and as I was not afraid of water, I soon learned. He taught me all the tricks of driving, breaking jams, where to begin the right swing or left swing or center, and many other things which helps to make a driver. If men had been plenty, they would likely have tried to dock me on wages, but as they needed more drivers, they were willing for me to learn. They paid from $2.50 to $5.00 per day, as it was dangerous work and so the wages were high. I was the only kid in camp, and they as old lumber jacks did have lots of fun at my expense. I had lots to learn if I expected to be a good driver.

I was going down the river the same way I was told to ride and follow up to a certain bend. I was going along nicely when I struck a rock unnoticed, and in I went, not even taking time to get a few turns out of the log. In I went just like a big bull frog. It was a cold morning, and the water nearly took my breath. I got my lunch wet, but did not take time to think of that for long. My peavey had gone to the bottom where I fell, and the logs were running thin along there. I had to take the one I was on before. I was so cold and fingers were numb. I swam up to the side, which I knew better, but did not take time to think. I soon found out my mistake, for when I would try to climb up on the side, it would roll and put me under every time or send me backwards. I now went to end of the log, and had nearly gotten up, when my wet suit and the cold air forced me back. I now struck out for the nearest shore. I had to get there, sink or swim.

I was glad when I reached the bank. I built a fire, as I always had dry matches. I carried an aluminum waterproof match safe, which would float in the water any length of time and yet be dry inside. After I had a fire built of dry limbs, I made me some hot tea. My tea was wet, but that did not hurt it. I ate some wet bread and meat and my boiled eggs were just as good as before the bath.

I now struck out for my old home, Captain Jack's camp, for we were near it. I borrowed a peavey of his and when I was through, I returned it, but did not pay for the one I lost for no one knew I had lost one, only Captain Jack. It was the last driving I did on the Swan River.

I now went back to camp for I wished to put in a good fall hunting in the open hills along the noted Mississippi with Captain Jack, Hays, and George Cox. We went among the lakes of Van Duse, Black Face, Long Lake, and Hay Lake.

At Swan River there was a hotel that was owned by McDonald. A few months before this, I had worked there. He was improving the station of Swan River a little. When I first came, there was only a log post office. Now it was a frame building and a fine depot had been built and several buildings had gone up.

Swan River Logging company Office at Mississippi Landing, Built in 1892

Courtesy of Aitkin County Historical Society

Swan River Station was four miles from the river by the same name, and Swan Lake was at the head of the river. The Swan River Logging Company ran a railroad up in the north country and crossed the Great Northern Railroad. The logs were rolled into the Mississippi and were driven down river.

(And so) we hit out for the hills. We went by way of camp and stayed overnight. In the morning each of us had a pack load to carry besides 500 or 600 cartridges a piece and our rifles. The packs were loaded with a tent, blankets, salt, pepper, and a big bag of army hard tack. While hunting, we each carried a compass, a lunch, and a belt full of cartridges, knife, and hunting ax. I wore my buckskin on such occasions, but the rest dressed in wool clothes, for they did not make a noise like cotton or duck clothes.

One man had two gallons of the finest whiskey, which hunters were never without, as all would take a sip each night as they came in tired and hungry. Of course, they wouldn't force any to take it if they did not want it, but it was seldom that a fellow like that was seen in such a wild country. If you refused they would thank you, for it meant that much more for them. They thanked me quite a few times for I did not drink at all and felt just as good the next day as they did.

I killed my share of the deer. We had one big frying pan in the party, there being four of us. It would hold enough for all by frying two or three times normal size. You would be astonished how much a hunter can eat, and how good the venison tasted, salted nice, fried nice and brown being well chopped by our hunting knives on a stump. Then we would plop down on our blankets, which had a nice bed of spruce boughs under them. We would eat venison, hard tack, and pure coffee without cream or sugar, for hunters never carry such. I must say, I never felt better in my life than when I was hunting and camping.

When we got ready to travel, we picked up our stuff and went on to a change of hunting grounds. We had everything in order. Everything in Captain Jack's party always went just so, and no one person had more than his share of the work. Captain Jack led our party. One would cook, one got the water and meat ready, another got wood for the night. We had some nice fires in front of our tents in a grove of pine or spruce near a lake or fine spring.

Every night was one to be remembered. The reflection of the fire in our tent gave light and warmth, and the birch wood would burn steady all night. A fire would hardly have to be started up once a night. We generally took turns in keeping the fire. If it was cold weather, one would watch until midnight, when another was called to take his place, and there would always be a nice bed of coals to cook breakfast on.

Every fellow killed deer for himself and no two went together, though we would sometimes hear the rifle reports near us. One day, I thought they were shooting at me, for there were two rifles banging away, and the bullets were more than whizzing over my head. I got out of there as fast as I could. I always like music, but I didn't like that tune.

When I got to camp I asked who had been shooting at me, and they all declared they would not shoot at "Buckskin Bert" for they said I was too good a shot myself to take that much risk. They had called me that every since I had come back from the Sandy Lake Reservation. I asked what two rifles were shooting about four o'clock. "Red" (as we called him meaning George Cox), and Jack spoke up and said they were shooting about that time at a porcupine up in the top of a pine tree, but were off west about two miles. I said two miles or none, they made me dance out of there. I told them they had better drink my share of the old rye so they could shoot better and not have to waste so much ammunition.

Some days later, we hit out for old Swan and reached camp before noon. I hired out to Captain Jack for $35 per month. He took my share of the deer, except the hides and horns which I took to Sandy Lake and had them tanned. I also got a share of the great moose antlers for my run from the moose.

Captain Jack was going to log again that winter over in the Hay Lake country and would have to build a new camp. We did not start over before the lake was frozen solid. When the lake had frozen solid so the horses could cross on the edge, we started for Hay Lake. It was quite a job to move everything over, even all the winters hay had to be hauled. It was quite a job, but not when a lot of woodsmen got hold of the stuff. It was not handled like they handle fine furniture in a factory, but was thrown or knocked around in any shape to get it there.

We got as far as the lake in safety, but when the horses got out about ten feet, the whole thing, load, horses and all, went through the ice. There were a number of springs close, and they had not frozen solid. Jack was not driving because if he had been, he would not have drove there, for he knew it was unsafe. There was a mess for a while, but as we were near the shore, it was not so bad. The water came to the top of the sled, and the horses were floundering around breaking more ice. By getting into the water, we managed to get the horses unhooked, got them to land, hooked a log chain to the tongue, and dragged it out. The sled was a mess. The water froze solid on our clothes so we dared hardly move. We finally got around where we wanted across the lake. We got ready to build, shoveling away the snow. Some went into the timber to cut logs to build with while teams were hauling up the timber. A place had to be cleared where the camp was to be set.

One evening, Captain Jack said, "Bert, we have got to have some of our moose meat or venison. We have got to have all we need so there is enough of it for all winter." He asked if Red and I would go after some. He said we could have four horses to pack the meat on, as there was no road in that country, only a few narrow trails where a horse could barely pass with a pack. We took a pair of blankets for we would have to stay overnight.

We agreed to go. In the morning we started bright and early, each leading an extra horse with a pack saddle on. We got to where our big moose was and found that the coyotes had been bothering around. We decided to pack the meat in the morning so we tied or picketed out the horses on a ridge where there was plenty of level ground. We gave them grain we had brought along, as the grass was snowed under and frozen like a rock.

We threw down our blankets, built a fire, cooked some meat, and ate heartily of such as it was. I had brought along my rifle as it is always safe to carry a rifle in a wild country. A fellow's pistol isn't as reliable. Red had left his at camp, and we were both glad that I had brought it. We thought the coyotes would eat us up before morning. We could see them running round in the dark, and they kept getting closer. The noises they made would make a man's blood run cold, but by firing a shot at them once in a while, we were able to keep them at bay. We had meat roasting, and the scent attracted their curiosity to have some of it.

I was overly glad when morning came. I was done with that hideous coyote night. Anyway, it was now in the past. We found our packs were full when we got the moose meat and venison stored away on the backs of our two horses. We started for camp by way of Black Face Lake, which was better traveling. We reached camp without any mishap, and Captain Jack was glad for a change of venison. We kept on packing until we had our meat all home, and hung up near our camp frozen hard. When we got all our game hung up along the camp, it made a pretty sight. When meat was wanted, we carried a deer in and hung it up in camp and let it thaw out a little. Then we would skin them and let the cook tend to the rest.

Now we had to build camp. We lived in a tent until about Christmas. Some readers may think it impossible to live in a tent when it is 20 or 25 below zero, but it was nothing thought of in that country. The snow was over a foot deep, and there was bad stormy weather. We lived as comfortable in a tent with a big birch fire in front. (It was) as we wished to live, and (we felt) better than if we were in a first class hotel. Of course, it depended on whether you like camp life or not. On windy nights, your eyes would be nearly smoked out, but that was included in camp life and didn't cost you anything extra.

We had fried venison three times a day and good biscuits baked in a camp oven, and we had a place where we cooked and baked beans. We had a hole dug in the ground about two feet deep just under where we built our fire every night. It would fill up with live coals clear to the top. After we had parboiled our beans, always making the kettle clear full, we had put a lid down that fit tight so no dirt would get in. Just before we went to bed, we would take a shovel and dig part of the coals out of the hole. We then set our kettle of beans with chunks of fat venison on top. Then we covered the sides and top as full as possible, and then we built our fire over it as usual. In the morning, we raked away the coals, and we found as good a Boston baked beans as can be had. Fried venison, biscuits and baked beans was what we lived on while camping.

Every night the wolves were howling louder and louder. We built our camps out of logs and made floors out of hewed poles. Our camp was only intended for 15 men and was small, but was comfortable. Before Jack went out to look for a crew of men, he sent me over to the camp on Swan River to build up a fire so a large bin of potatoes would not freeze, as it had turned suddenly cold. It was pretty cold and I wanted to get to the camp as soon as possible. So like most fellows, I thought myself a great woodsman. I could not get lost if I tried. I didn't even take my compass, only my rifle. I didn't take the road, but struck off through the jungles and hills in the direction of camp. As the country was so rough with so many bluffs, no road had ever been made through there. The road went four or five miles out of the way, so I ate lunch and got started. I traveled towards camp all day and finally found myself near the Swan River. I took up the river, but the river being so crooked was going miles out of the way.

Finally about dark, I thought something was wrong. I knew I ought to have been to camp a good while ago. It was turning bitter cold. As I was wandering around, I fell through a sink hole clear to my waist before I could recover myself. I caught hold of some brush, and in that way, I got out. The reader can imagine what a fix I was now in, the minute I came in contact with cold air. I was frozen stiff, but I trudged on hoping to find some land mark I knew, but all in vain.

I was lost to myself and everybody else. I almost gave up in despair. The sense or thought of being lost, I believe, would in a few days drive the strongest man crazy. It is a feeling I cannot express in words. I had left my matches, compass, knife, hunting ax, and all inside my buckskin suit when I had changed to woolen clothes after my fall's hunt. I was in a bad fix, with no fire to keep from freezing. I must keep moving I said to myself. I felt the cold, and the wind just went through me and took my breath at every start. If I had a fire, I would not have cared for I had my rifle to kill food with and could find my way out in the morning. If no other way, I could back track myself, but I had likely crossed my track so often it would be hard work, but I would freeze before morning. I felt the cold worse now. Being wet, it had frozen to ice. I even froze so hard that when I bent my knees, the pants were froze so hard that they broke.

Would I ever see another day? If only Captain Jack knew that I had not taken the road, he would be after me. I wished by noble dog, Beaver, was here to guide me out, but more as a companion. I felt so lonesome, I was not much loss if I did freeze, as no one depended on me, but yet I hated the thought of freezing to death. All along I hoped for the best, for many had been lost in this same country and found their way.

Yet I kept plodding along to keep from freezing. Now and then I would fire a shot, though I had little hopes of being heard. The only person being near our camp was a man that worked for Jack sometimes, but yet he was sure to be at home. He and his brother were hunters and had lived there many years. I had fired a good many shots, plodding along at a very slow pace, as I could hardly walk from the intense pain on my feet. But alas, I found my feet both frozen solid for they were numb and no life was left in them, no feeling, and they would pain me no more. Now my fingers were kept warm by the occasional firing of my rifle, as the barrel got warm, but would soon be as cold as ever. I felt like throwing myself down in despair. I had wondered far into the night, and the cold northern winds were howling the most shrieking noises, only adding horrors to my fate.

Each hour seemed like days. I was just about done. I only had one more shot. I trudged on again. I don't know how many times I went around that circle as lost men do, but when I leaned against a tree thinking about all the mean things I ever did, I had a feeling like I was getting my punishment. Now I fired my last shot into the air with despair and gave up all hope. But when my hope was gone, I heard something. What was it? A rifle shot? Could it be true? It must have been the echo of mine. Who could be out here in this deserted land of hills?

I had really heard a rifle shot, but did not have the opportunity to answer with another shot. Then off to my right from the direction the shot came from, there I could see a light through the window, and how glad I was when I found I had reached help at last.

I was well acquainted with the boys and made myself at home, but my feet were frozen stiff. They cut the rubbers off of my feet and also the socks, for they were frozen fast to my feet. I was in bad condition. Had it not been for the boys, I would surely have lost both my feet. They worked with them a long time. I know not how long, for I fell asleep while they were tending to my feet. They kept my feet in snow and kerosene, all the time rubbing my feet. I soon woke up from the intense pain. My feet were coming to, and they were beginning to thaw out. It hurt a good deal worse than it did while they were freezing. I never felt a worse pain in my life. It hurt worse than the time the stump pulled me in the fire and blistered my feet all over. I thought a burn was bad, but this was the awfullest experience of torture I ever endured. I had frosted my cheeks and nose, but a little snow rubbed on them brought them out, but my feet were in a bad condition. It froze my heels mostly, and I suffered about two weeks of intense pain. I could not bear my weight on them. I was laid up so I couldn't do a good day's work for nearly a month, but in two weeks I was able to get wood and work around the camp. I would wear no rubbers, but wore moccasins the rest of the winter. Every time my feet got cold, it would set me crazy. My feet would never stand the cold like they did before I froze them. I was careful to take my compass and matches after that.

Along toward spring, our neighborhood was surprised by a band of redskins of about forty warriors out for a good old time, as they call it. They did not molest our camp, but had a wicked little fight in a camp two and a half miles east of us. Captain Jack and myself were out cruising timber all day and were just coming to camp about six o'clock when Jack called my attention to a peculiar yell as that of a wolf off to the southeast of us. I was deceived all right. I couldn't tell the difference. Captain Jack asked me if I ever heard a war whoop or a real Indian yell when they were in their war paint. I told him I guessed I had, but did not remember it enough so I could tell another.

When Captain Jack informed me that there were Indians on the warpath around us, I thought he was only testing my bravery, and I didn't dream he meant it. I acted as if I believed him and was just as cool as I could be. He seemed to admire my cool head, but he said this is not good for us to be empty-handed though we have brave heads, and at that, he started through the woods like a deer. I soon made up my mind what Jack had said was true, for just now a most piercing yell I ever heard came from a score or more of reds. They had evidently not seen us. We made for camp, but before we reached the lake, we heard another band to the north. They were surely going to do some mischief. It was beginning to snow and when we got to camp, we could hear the band getting closer to each other by their yells. Our whole camp had been hearing the noise, and supper was eaten in silence. We didn't know what would happen before morning.

About eight o'clock we heard the very noise of Indian battle. The rifles were cracking on both sides, and in quick succession, a continuous shooting lasting only a few minutes. Then within the hour the sky lit up with the fire of the camp.

We had a great notion to go to their aid, but we didn't know if there were some reds scouting around right now, and we didn't have much ammunition. As it was, the country had not been invaded with them for some time though they had been over this country in small parties. Every spring the Indian agents were likely refusing them food or some other thing and that made the reds rebellious and so they had skipped the reservation. Red, Jack, and myself were the only ones who had any ammunition to speak of. We had only five or six rifles and about as many pistols of which concluded our weapons.

The Indian trail was only a half mile from the lake, and we expected an attack. If an old buck got 20 or more young Indians around him, telling them of the fun of taking scalps and fights he had in former days, it's hard to tell where they would stop until an army got after them.

The camp attacked already belonged to Ed Hays, who had hunted with us the fall before. We stood guard all night. It was snowing very hard, but when Indians are least expected is the time they come, do their mean things, and then get to the reservation where they are protected by the government. If caught outside, the palefaces would spare no mercy, especially the great woodsmen when such mischief has been done, for they will shoot them down. After they had fired the camp, the Indians scattered and made for the reservation. There wasn't a one to be seen save a few dead ones.

I slept with my rifle in my hands dreaming of Indian fights and such. At the very least noise, I would wake with a start, for I didn't want my scalp taken. I was glad when morning came, as I felt like I had been fighting Indians all night.

The next morning Captain Jack, myself, and Red went to see the ruins. We found the main camp safe, but Hays was looking pretty angry. It certainly looked like blood shed. It was a sight I tell you. A half dozen reds lying around, the hay all burned, and the stable burned with all the horses. They had killed and scalped the cook and cookie. The men could not get to the cook camp, and thus the two cooks were shut off, fighting with butcher knives. It was the very scene of destruction. Everything was turned upside down.

Hays and Pancake (George Washington Pancake from Goodland, a noted hunter) are crack shots and were for ganging a party to punish them at once. Hays had a ball graze on his head. They blew out the lights so it would not give the reds the advantage. Captain Jack said he would like to see the Indians caught, but did not know whether he could leave or not. After a little thought he said, "Hays, I have hunted with you several times, and I'm going to help you out with this matter." I asked if I could go, but Jack wished me to stay at camp. I told him I would join the crowd, and it would not be anything out of his pocket.

Red, myself, Hays, Captain Jack, Pancake, and a party of Hay's men, who had rifles, struck out. It was not a hard matter to find the tracks of the Indians for moccasin tracks were thick. We would not waste time here for we would strike for the head of the Prairie River where the Indians would cross. The Indians were now several hours ahead of us. When we arrived, we found they had gone by. But after a time, we came to where they had a fire built, and there still was a fire, so we knew they were not far ahead. We had to keep look out, for if a band of 40 would surround our little party, we would have little show. We divided into two parties where the Indians had separated. One party had gone north. Hays took one party and Captain Jack the other, each supposing to meet at Serca Lake, a full mile this side of the Chippewa Reservation. In the end, we never got a one. The Indians were too far ahead of us. We had our minds made up that if ever we saw a red face peering through the brush, we were to capture him alive, if possible, and roast him over a slow fire. For if the main band heard it, they would be more careful.

That was the last trouble I heard of while there. While I was on the reservation, I would never dream that they would cause so much mischief. But if a paleface got quarrelsome, they would chase him out with knives in the hands of the skilled red man.

Lots of trappers made their living by giving them whiskey. One reason the Indians break out is the fault of the Indian agents. They get careless in providing them with food. The Indians have a good trait. If ever you do one a favor, he will always remember you and will help you out if you get in a tight place. But if ever you play him a trick or do him an evil, look out for him as he will never forget it.

Long toward spring, a large bear kept coming every night to our garbage pile where the cook threw all the waste food, deer heads, and the like. Several nights we heard him out there. One night we had some fun. We all rushed out of the camp yelling, and if ever a bear did run, he did. Down that hill through brush making as much noise as an elephant, and then we would turn and run back.

The nosy devil would turn and come back, as bold as if it was a common thing. We wouldn't be no more than in camp when the cans and stuff would be rattling to beat the band. We ran him down the hill several times, and then Jack said he would puncture him if he got too gay for himself. He started to enjoy the sport of running downhill with us after him and would never fail to come back. Captain Jack took my rifle and pretty soon fired, and we heard him going down the hill. He let him have another. He was a large black bear and his fur was fine.

I worked until about the 27th of March and having contracted to work for Leir W. Rood in Livingston, Colorado, I left the wilds of the north for civilization for a few months.

And thus ends the story of my hunting expedition to the far north. I left my partner and spotted Beaver with Captain Jack until such time as I should call for him. I visited the docks at Superior and the shipyards. I saw the large lake steamers, but they looked quite different, for their rigging was all off and they were frozen in. The masts all are quite a different scene from the fall when I came up. Thus I bid farewell to that country and its acquaintances.

Bert Gray came back to northern Minnesota and lived out the rest of his life here. He settled on a farm on the southeast quarter of section 24 in Splithand Township. Bert became good friends with the Simons Family. He died of tuberculosis in 1913. His memory lives on.